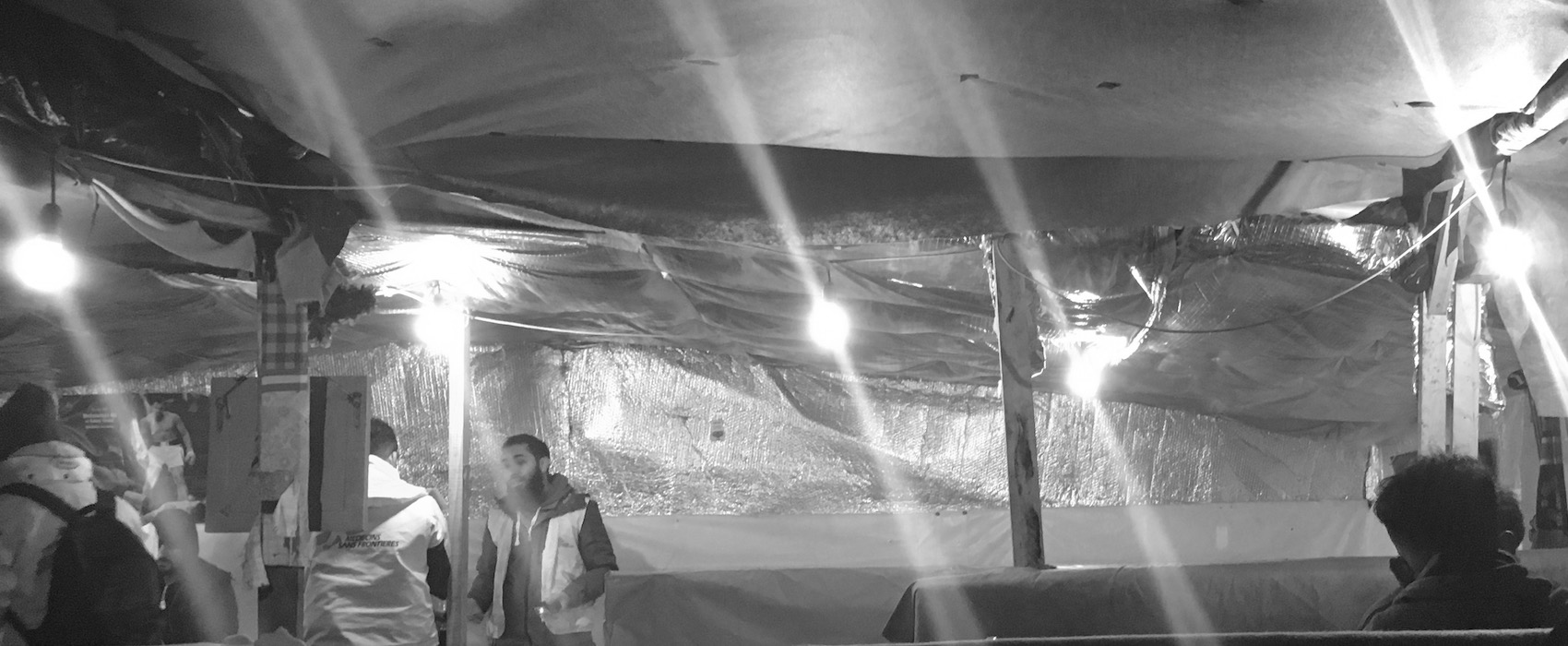

In a small cafe tucked away in the corner of Guy’s Hospital, I thought of a place where I went to warm up and drink coffee during my recent trip to the jungle camp in Calais… There are a number of restaurants and cafes there, set up in makeshift huts, along with kiosks, shops, barbers and hairdressers on what’s called the ‘high street’. The place that sprung to mind was our last stop before we headed home – a large wooden hut that offered much-needed, though scant, warmth and hot, sweet milky chai when the cold was getting the better of us, rendering us incapable of deciding what to do next.

Ostensibly there was little similarity between the cafe area where I was sitting waiting for a friend who had a hospital appointment and the bleak haven where, coat still on, the process by which the cold and bitter wind seemed to be burrowing deep into my body could at least be halted.

The slightly cramped corner of the busy reception area of Guy’s hospital bore no physical resemblance, and in fact the heat was slightly stultifying, but there was something about the atmosphere, brought on partly by the fact that people were forced to share tables, that brought to mind the cafe in the Calais camp. The wooden hut epitomised the word ‘functional’ but despite the colourless, cold of the wooden interior, it offered relative warmth in a shared space, a place to go to mingle, a place where camp residents, including all those, Brits in particular, who had gone there to work in the camp could mingle, where people greeted those who came in, moving to different tables to catch up with others.

Those who huddled around tables on the heavy stools seemed more open to one another than you normally expect in a London cafe.. One man started a conversation with a woman about the book she was reading, another woman smiled warmly and said ‘Of course’ when a young man pushing an older man in a wheelchair asked if they could join her. Small things, really, but it did seem there was something different about these people drinking coffee and preparing for the next stage of the visit. The gentle concern in people’s voices, the attention to small details and small acts of affection and concern that demonstrate much deeper emotions, love, concern and fear.

In an essay called Knot, which is part of a collection called The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit says that illness “mitigates solitude…in that it attacks any notion that you are separate, autonomous, and independent”.

You require bone marrow or blood from another, the care of experts and of the people who love you. You are made ill by a mosquito or a virus, or an unknown environmental toxin or by an aberrant gene you inherited or some exciting combination of these things. You cannot ignore that you are biological, mortal, and interdependent.

Perhaps the common experience of being in that windy ramshackle camp, the challenging environment, the sense of abandonment, had a similar impact on the people huddled in wooden huts in Calais as illness did in the hospital. Perhaps people there and the cultures they were from had different attitudes towards themselves in relation to groups, to the other. Whatever it was, there was a sense of connectedness in both places that I recognised in Solnit description of a “final masterpiece” created by her dying artist friend Ann, “a vast wall map of white plaster topographical reliefs of islands” connected by fine red string in the hospital where they were both patients.

I think of that piece as an elegant assertion that everything is connected. Each of us is an island of sensations confined to the realm beneath our skin, but a great deal of migration and importing and exporting connects most of the islands to each other. It does if you can locate yourself in an archipelago or trace the lines to where they reach others and the lines whereby others touch you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.